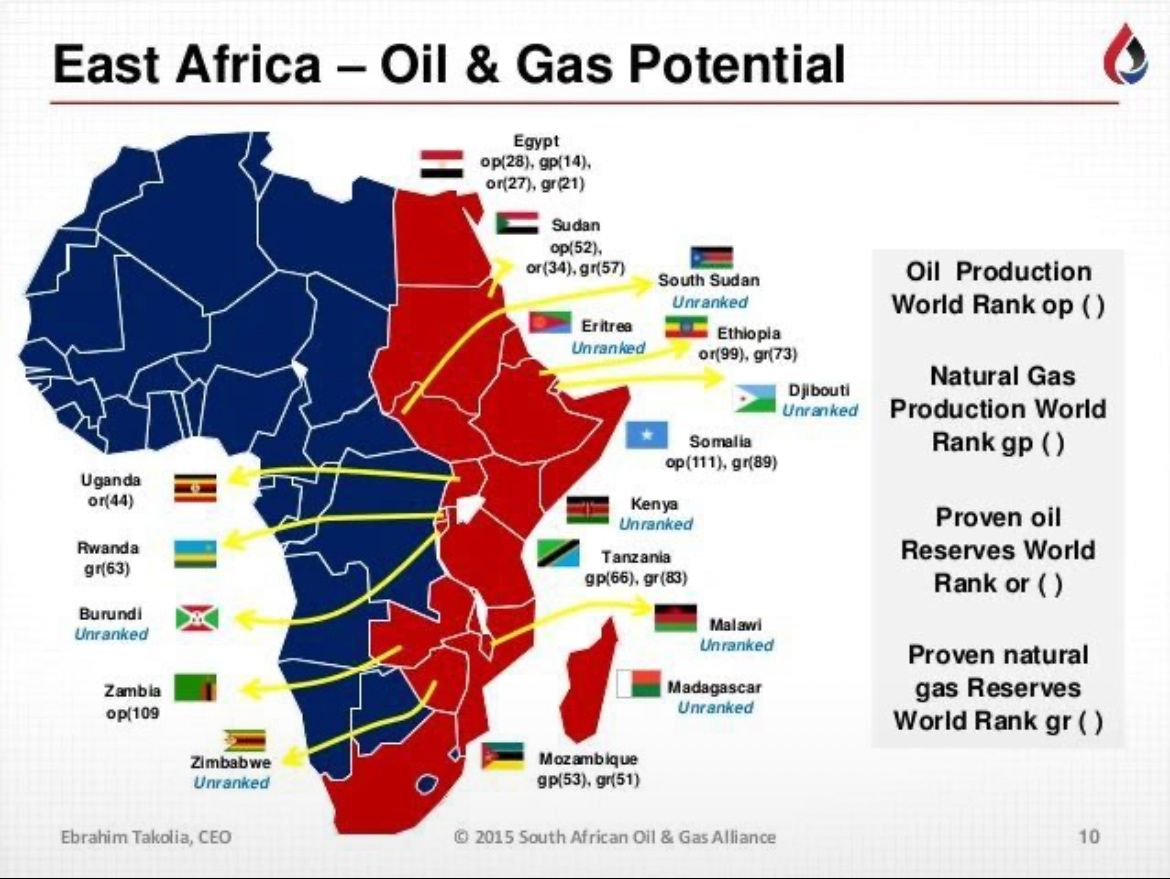

East Africa is emerging as a significant player in the global oil and gas sector, with countries like Uganda, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Kenya making substantial discoveries. These resources hold the potential to transform economies, but they also bring forth challenges related to infrastructure, governance, environmental sustainability and security.

Uganda’s Albertine region is estimated to contain about 6.5 billion barrels of oil, with recoverable reserves between 1.4 and 1.7 billion barrels. The Tilenga and Kingfisher oil fields are central to Uganda’s ambitions. To facilitate exports, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) is under construction. Spanning 1,443 kilometers from Hoima in Uganda to Tanga port in Tanzania, it is set to become the world’s longest heated crude pipeline, with expected completion by July 2026.

Mozambique and Tanzania have made significant offshore gas discoveries. Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin holds an estimated 100 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, while Tanzania’s reserves stand at around 57 trillion cubic feet. These finds have attracted major investments, including TotalEnergies’ $20 billion Mozambique LNG project, targeting exports by 2030.

However, developing these resources requires massive infrastructure. Projects like EACOP have faced financing setbacks as some international lenders withdrew over environmental and human rights concerns; some of them raised by #StopEACOP | Stop the East African Crude Oil Pipeline activists. As of early 2024, only a few financiers, including Standard Bank Group and China’s SINOSURE remain committed.

Regional efforts are underway to boost cooperation. The East African Community (EAC) is pushing for joint infrastructure projects, including a 784-kilometer refined petroleum pipeline from Eldoret, Kenya to Kampala and Kigali—aimed at lowering transportation costs and improving energy security.

Governance remains a critical issue. Uganda scored 49 out of 100 on the 2021 Resource Governance Index, citing weak transparency, no public licensing cadastre and non-disclosure of contracts. These gaps risk undermining resource management and public trust.

Environmental concerns are pressing. Projects like EACOP traverse ecologically sensitive zones, including Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park. Civil society groups have warned of risks to biodiversity and communities. Petroleum Authority of Uganda has initiated safeguards, including public consultations and environmental assessments.

Security threats further complicate progress. Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region faced insurgent attacks that halted the LNG project in 2021. Although regional military intervention has restored some order, threats persist and could delay project timelines.

Despite the hurdles, East Africa’s oil and gas potential could fuel long-term economic growth and regional integration—if managed transparently, sustainably and securely.