After the dust had settled, the smell of cordite had been blown off by the seven winds and the jubilation had ended, the victorious National Resistance Army (NRA) had to settle down to the business of making Uganda great again.

In January 1986, after a five-year struggle, President Yoweri Museveni and the ragtag NRM took over Kampala. At his swearing-in, Museveni promised a fundamental change in the history of the country.

The economy, which had been battered by years of civil war and mismanagement, was a shadow of its glory days in the 1960s. And, as a matter of urgency, had to be resuscitated if the fundamental change was to have half a chance of materialising. Impoverished economy.

According to a World Bank report of the time, the GDP per capita stood at $230 (about sh865,981 today) or about 60% of the level at which it was, in 1971. The formal sector had ground to a halt, with 83 factories surveyed at the time, only 10 of them were operating beyond 30% capacity while another 29 were shut down.

Agriculture, which had regressed into subsistence, accounted for 40% of GDP, coffee accounted for more than 80% of export revenues and more than half the revenue collections (they used to tax coffee exports those days).

Coffee production stood at 70% of the 1965 levels at 160,000 60kg bags and cotton production had collapsed to 7% of 1965 levels. At a personal level, public service salaries were so bad that at the lowest salary level, the monthly wage was not enough to buy a bunch of matooke.

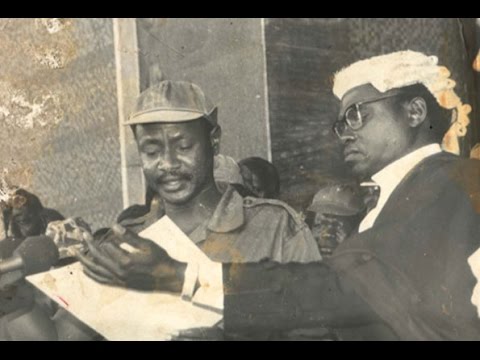

You cannot, therefore, envy Prof. Ponsiano Mulema, the NRM first finance minister, under whose brief it was to jump-start the economy. 1986/87 budget reading It was not a good omen that the 1986/87 budget was read at the end of August, months into what would have been the new financial year.

The financial year runs from July 1 to June 30. It lent no confidence in the situation when the finance minister admitted that accurate figures about the economy’s performance were hard to come by. “The low level of production, both in agriculture and industry, was reflected in the trends of the GDP.

It was, however, not possible to get reliable statistics. During 1985, it is estimated that the GDP fell by 5.5%. The monetary economy showed a decline of 3.9% during the same period, while the non-monetary could have declined by up to 8%,” Mulema told the National Resistance Council (NRC).

“It is not possible to get accurate figures for the non-monetary economy in the absence of detailed statistics. The decline in this sector could have been moderate or substantial, but it can be assumed that as a result of massive smuggling that, was going on at the borders, the decline in production in the peasant economy could have been more apparent than real.”

Mulema also reported that the previous year’s budget had gotten out of hand. “The budgetary situation during the year 1985/86 was abnormally difficult. The budgetary performance was more absurd than ever before,” he said, his frustration palpable many years later.

The budget jumped by 43% to sh514b from the earlier planned for sh357b. Revenues, fortunately, followed suit, coming in at sh402b against the earlier projected sh313b, but still left an sh104b hole in the budget to plug.

Expenditures exploded during the budget because of the new requirements for emergency relief for the Luwero Triangle, Arua, Moyo, Moroto and Kotido, provision of free education for pupils in the above war-ravaged regions and increase in defence spending – soldier payrolls and logistical requirements for the military mopping up exercises.

There was also depreciation of the shilling, which affected the cost of foreign currency payments, such as loan repayments, essential imports, and travel abroad. Inflation hits nation With increased government spending came inflation.

Official figures show that in 1986, inflation was recorded at 143.8% and spilled over into the next year, where it came in at 215.4%. To make sense of these numbers, it means that in 1986, prices were doubled every six months, accelerating further and doubling every three months in 1987.

This meant that if you paid sh1m as school fees in January in 1987, you would pay sh2m in the second term and sh4m in the third. Other historical factors aside this, partly explain why Ugandans gravitate towards business because, in an inflationary situation, you can raise prices – to some extent this is true, but it is better than being locked into a monthly salary, which is unresponsive to price changes.

Mulema took this into account and managed a 50% increase in the wage bill, with the biggest pay hikes going to the lower cadre. “This will, of course, not bring significant relief to the workers as the prices will be high for all of them.

The Government, however, intends to take further measures in the near future, to bring about a happier balance between goods and services on the market, and aggregate demand,” he said.

“More meaningful salary increases will only be possible when our production levels and the tax base expand and when the Government has trimmed down the establishment, where excessive staffing exists,” he said, because even than, the tax base was narrow, much narrower than it is today. Revenue collections The ratio of revenue collections to GDP in 1986/87 stood at about 5%.

In the current financial year, the projections are that with collections of about sh16 trillion, the same number currently is about 15%. Which is still low as the sub-Saharan average is 16%. Kenya’s ratio was 15.6% in 2017, while Mauritius was 18.5% and South Africa 27%.

But you had to sympathise with the minister because due to the collapse of the formal sector, his scope for taxation was miserably small. It was reflected in some of the tax rates he found in effect. Despite his urgent need for revenues, the minister reduced the corporation tax to 40%, from 50%, for companies in industry and agriculture, while raising that corporation to 60% from 50% for banks and other financial institutions, but not insurance companies.

It is inconceivable that companies today would be required to surrender half there profits to the Government and it probably encouraged a lot of tax evasion at the time. He, nevertheless, raised import duties to as much as 100% on petrol, 50% on paraffin and 20% on diesel.

He also announced a raft of increases on beverages, cigarettes, and road licence fees. The Government was so hard up for cash that they decided to flag off a fleet of buses to raise an additional sh4.4b, which was more than they expected from the parastatals in dividends, about sh4.1b.

Predicated holes in budget Despite his best efforts, Mulema was projecting an sh349.7b hole in his budget as he proposed to more than double the budget to sh1,127.5b, prompted by a doubling of the recurrent budget, which included salaries and development.

He definitely tried to factor in the rising prices in his projections, which, in his doubling of the budget, he must have known would not help the cause of reining in the galloping inflation. The Government still had more than 100 state enterprises that were gobbling down money.

He provided sh22.7b to support them, of which sh7b went to Uganda Airlines alone. Relatedly and what was also bleeding the Government dry, was that it still had a monopoly on produce marketing.

Mulema announced that the Government had just bumped the prices they were paying to farmers for certain export crops, presumably coffee and cotton, and reaffirmed the Government’s position to pay farmers higher prices to incentivise greater production and narrow the inequalities between rural and urban populations.

However, with no control of market conditions, this was merely a wish. “Because of the current condition in the international commodity markets, it is impossible for the Government to review upwards the prices currently payable to producers. As suggested above, with regard to world prices for coffee, the Government is only making an effort to maintain prices to the farmer at the level at which they are now. Price increases are, therefore, impossible in the circumstances,” Mulema told the house.

Nothing more than this reality brings into sharp focus the challenges of the new Government. Infrastructure The Government urgently needed to raise revenues to finance the rehabilitation of the entire infrastructure network, to pave the 1,500km of trunk roads for a start – an inheritance from the colonial administration, increase school enrolments, improve health services and, as if that was not enough, to quell insurgencies that were flaring up in the north and east of the country.

Such demands dwarfed the revenues they could marshal as listed above and, in a classic case of desperate times call for desperate measures, they set the money printing presses rolling to disastrous consequences. Inflation shot through the roof, peaking at more than 200% in 1987. Inflation happens when too much money is chasing too few goods.

Mulema mentioned it in his budget speech that it was a clear issue of production having collapsed and, for years before he made his speech, the Government had been printing money like it was going out of fashion. The challenge was clear: to kick-start the economy, the country had to produce more.

More food. More tradable goods. To do this, they needed money to pay incentives to producers in agriculture and industry, as well as the services sector, tax them and spread the wealth.

And they were not operating in idle situations; with disease, poverty, and war all around, it was hard to see how they got anything going in 1986. This called for hard decisions, some so unpalatable as to jeopardize the whole NRM project.

Source – New Vision